#HenleyMBA:

By: Derek Jansen | December 2017

If the Henley MBA is about any one thing, it’s about learning to analyse well. Therefore, it’s no surprise that the analysis chapter/section of most assignments is typically allocated the largest percentage of the marks. In this article, I’ll discuss how to write a strong analysis chapter that earns marks.

Dissect your introduction and analysis.

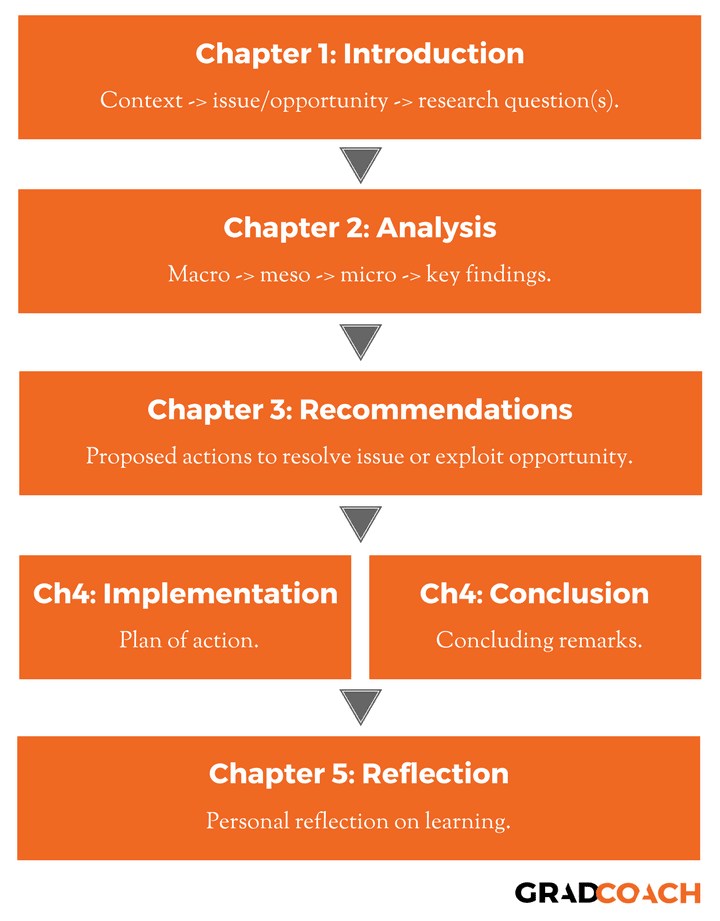

While some assignment briefs provide a rough outline of a suitable structure, this is typically just a guideline, not a directive. Therefore, it is best to follow the standard academic structure below:

*Some assignments will not have an implementation or conclusion requirement.

In particular, your introduction and your analysis should be separate sections/chapters, as they serve distinctly different purposes. The introduction sets the context and justifies the focus of the assignment, including the research questions. Be sure to read this post on the 5 essential ingredients of a strong introduction chapter).

The analysis chapter, on the other hand, should focus squarely on analysing the problem/opportunity with a view to answering the research questions you set out previously. Keep them separate and your document will be easier to read and your argument easier to understand – both of which are essential for earning marks.

Right, with that out the way, let’s move onto the actual contents of the introduction chapter.

#1 – Outline your analytical approach.

While you would have provided a high-level overview of your approach to the research in your introduction chapter, your analysis chapter should start with a slightly more detailed outline of how you approached the analysis. The objective here is to give the marker an idea of what you analysed (which variables), why (justification) and how (with which theories/models/frameworks). This shouldn’t be lengthy – just enough for the reader/marker to understand where they’re headed. For example:

“The analysis commences by assessing the impact of the macroeconomic environment on the key issue using a PESTLE analysis. Next, the microeconomic environment is analysed, with a focus on competitive analysis utilising Dibb and Simkin’s (1996) competitive positions proforma. Lastly, the firm’s internal resources are identified and valued using Barney and Hesterly’s (2006) VRIO framework. Conclusions are then drawn with respect to the research question.”

As you can see, this outline gives the reader a good idea of what was analysed, how it was analysed, why it was important, and how it was drawn together to a conclusion. Importantly, you’re not stating what the findings were – you’ll do that within the actual analysis.

#2 – Start macro, then zoom in.

With the analytical approach outlined, its time to start analysing. Typically, a good approach to your analysis chapter is to start at the macro-level and then progressively zoom into the meso and micro-level. In other words, you’ll analyse:

- Macro country-level environment – factors such as the political, economic, socio-cultural factors (i.e. PESTLE/STEEPLE dimensions).

- Meso-level environment – factors such as the industry, competitors, customers, suppliers, etc.

- Micro/internal-level environment – factors such as internal resources, competencies, people dynamics, processes and systems.

Naturally, how much you focus on each level depends on the assignment and the research questions. For example, a Managing People (MP) or Leadership & Change (L&C) assignment might focus primarily on the internal environment, while a Strategy or Strategic Marketing assignment might be more equally weighted across the levels.

Ultimately, every part of your analysis chapter should contribute towards answering your research question(s). There are almost always links to the research question(s) at all three levels, but don’t feel the need to draw up an extensive PESTLE analysis if the focus of your assignment is primarily internal. Highlight the key links, and leave out the rest. You can always place that full PESTLE in the appendix, as long as you present the key relevant points in the body of your assignment.

#3 – Analyse, don’t describe.

This is arguably the single most important practice when it comes to writing your MBA assignments. In fact, it’s so important (and so commonly not done correctly), that I’ve written a separate article on this here. Please take the time to read it, but here’s a summary for convenience.

Description = describing the situation, factors, forces, or variables. In other words, description means discussing the “what, where, how” and so forth.

Contrast that to:

Analysis = describing the impact of the situation, factors, forces, or variables on the key issue or research question(s). In other words, drawing out the “so what?”.

Naturally, there will always be a need for some degree of descriptive writing in your analysis chapter (and assignment as a whole) – you simply cannot explain a situation without describing! That said, as a rule, try to limit your description to a minimum by describing the “what” only as a way to get to the “so what” – in other words, use description only to lead to analysis.

Here’s an example:

#4 – Use models and frameworks purposefully.

All too often, I see numerous models and frameworks included in an assignment with no clear purpose or attempted justification. Understandably, students feel the need to include as many models and frameworks as possible to show that they’ve done their reading. This is, however, a mistake.

Quality, not quantity.

Simply put, less is more. A handful of carefully selected, clearly and logically justified and richly applied models and/or frameworks can earn a lot more marks than the quantity approach can. As with the matter of analysis levels discussed earlier, the use of models and frameworks should be dictated by the overall purpose of the assignment and the research questions.

Ultimately, you should be able to clearly answer the following question:

“What research question (or related sub-question) am I trying to answer by using this model or framework?”

If you don’t have a clear, concise answer to this question, the model or framework may not be all that well suited, and you should consider if there’s either:

- A better model, framework (or theory) to help you answer your question(s).

- A better question to be asking – you may well find that your research question(s) evolve as you undertake your analysis. This is perfectly normal and reflects your learning process.

Ironically, students often have a good understanding of how to use a model or framework but are not very clear on what its core purpose is (it’s “why/when”). This matter of why is critically important. Models and frameworks are simply tools. Markers want to see that you know both when and how to use the tool correctly. Use only the models and frameworks that have high relevance to your assignment’s purpose, and apply them deeply to develop rich answers to your questions.

Present the right way.

Choosing and applying the right models and frameworks is, however, only part of the puzzle. You also need to present them the right way. Again, I’ve written a comprehensive post on this which you can find here, but here are the key points:

- Introduce and justify the model in the preceding paragraph. Make it clear why you chose to use the model (i.e. why you’re using this tool for this job).

- Populate the model with the details of your situation. Don’t simply copy/paste a blank model into your assignment.

- Number, caption and cite the figure 100% correctly. Also, make sure you refer to the figure number in the preceding paragraph.

- Discuss the key insights from the model in the paragraph that follows – what did you find? How does this help answer your research questions?

Implement these four practices every time you include a model or framework and you’ll see the difference in your marks.

#5- Summarise after each large section of analysis.

If you implement all the above guidelines, you’ll no doubt cover a lot of content in a short amount of time. You will have presented a lot of data, and (hopefully) generated many insights. For the marker, this is a lot to take in. It’s the first time they’re reading your argument – it’s the tenth time for you.

Therefore, it’s very important that you summarise your key points/insights after each section of substantive analysis. Depending on the assignment, this might mean summarising after each model or framework, or perhaps each level of analysis (i.e. macro, micro, internal). There’s no hard word-count linked rule here – summarise after any large section of analysis to help the first-time reader (your marker) understand your argument.

Your summary can take bullet point form, or you may find that a framework from the module acts as a good summary tool (for example, SWOT). Some Henley students are concerned about using bullet points as this is highlighted as problematic in one of the assignment briefs. Long story short, bullet points are acceptable for summaries, but not for presenting new information or large pieces of analysis (which makes perfect sense). If you use bullets exclusively to summarise previously presented and discussed information, you’ll be fine.

Most importantly, make sure that you provide a summary of your overall key findings at the end of your analysis chapter. If done right, this summary should lay the foundations for the next chapter (recommendations). Ideally, you want to lay a very clear, rock-solid foundation here so that the recommendation is almost expected by the time it arrives. In other words, your analysis summary should link directly and logically to your recommendations. There should be no surprises!

For example, if, in your MP assignment, your key recommendation is going to involve revising the reward strategy within a firm, then your analysis summary should make it very clear that there are various issues with the reward system as it currently stands. You could even use a reward framework as an analysis summary tool to make the link more explicit.

Wrapping up.

In this post, I’ve outlined 5 points that, if applied correctly, should greatly improve the quality (and mark earning potential) of your analysis chapters. To recap:

- Start your analysis chapter by outlining your analytical approach.

- Structure your analyses from macro to micro-level.

- Analyse, don’t describe.

- Use models and frameworks purposefully and sparingly.

- Summarise your key points/insights after each substantive section of analysis.

Have questions, suggestions or criticisms?

I’d love to hear from you. Just leave a comment below, or get in touch with us here.

Don't Stop Now - There's More ✨

Qualitative Research Basics: The 20,000-Foot View

New to qualitative? Learn about the four key phases of the qualitative research process: data collection, coding, analysis, and writing.

How To Choose The Right Qualitative Analysis Method

Not sure which qualitative analysis method to use? Learn how to choose the right method for your specific research project.

Reflexivity & Triangulation In Qualitative Research

Learn how reflexivity and triangulation help manage subjectivity in qualitative research by enhancing credibility and minimising bias.

Trustworthiness In Qualitative Research

Learn about the four pillars of trustworthiness in qualitative research: credibility, transferability, dependability, and confirmability.

How To Choose A Tutor For Your Dissertation

Hiring the right tutor for your dissertation or thesis can make the difference between passing and failing. Here’s what you need to consider.

Thanks! great article 🙂

Pleasure, Shaun!

Brilliant article 🙂

Thanks, Vuyo.

whats your email address Derek

Hi Thabo

You can mail us on [email protected].

Derek

Hi Derek

Thanks for your insights !! Very useful indeed especially now I’m in that stage 🙂

Pleasure, Lawrence! Good luck with your MBA.

Wow, this really helped a lot. Great article!

It’s a pleasure, Atli! All the best with your studies.

Hi Derek

This is helpful, I dont know how many times I have given up on my studies. I find this article helpful. Great work.

Thanks.

Thanks for the kind words. All the best with your studies.

Great article, thanks Derek.

You’re welcome Anneline. Best of luck for your Henley MBA assignments.

Thanks Derek , this article as well as your others (intro and reflection) really helped me to establish a flow in my assignment and hopefully a good “golden thread” 🙂

Thanks for the kind words, Charl.